|

Index...

|

ra Frederick Aldridge, born on 24 July 1807 in New York City, was a groundbreaking actor who emigrated to the United Kingdom in 1824 and went on to enjoy a stellar career both here and in Europe. In 1865 he became a naturalised British citizen. He died in Łódź, Poland, on 7 August 1867 where he had been performing, and it is in Łódź where he is buried.

ra Frederick Aldridge, born on 24 July 1807 in New York City, was a groundbreaking actor who emigrated to the United Kingdom in 1824 and went on to enjoy a stellar career both here and in Europe. In 1865 he became a naturalised British citizen. He died in Łódź, Poland, on 7 August 1867 where he had been performing, and it is in Łódź where he is buried.

He was the first African American actor to achieve success on the international stage and was especially renowned for his portrayal of Shakespearean characters - notably Othello - but was equally at home portraying comic characters and performing songs.

In the period when he arrived in the UK, slavery existed in the Caribbean islands of the British Empire - known then as the West India colonies - and of course in America, the country where Aldridge was from. Its advocates liked to justify this vile practice by dehumanising Black people - essentially claiming they were more or less on a par with savages and that slavery was actually beneficial for them. The print media of that age, whether they opposed slavery or not, generally perpetuated the myth of white racial superiority. The prevailing view seemed to be that African people and those of African descent were "uncivilised"; and the only way for them to become "civilised" was for missionaries to convert them to Christianity; have their children educated in church-run schools and essentially imitate the ways of white people.

In the year that Aldridge was born - 1807 - the British transatlantic slave trade was abolished by an Act of Parliament that was passed on 25 March. However, this Act only stopped the purchase and transportation of slaves from Africa to the colonies of the British Empire. Here, the brutal, inhumane and degrading practice of slavery continued unabated. Some slave owners found ways to circumvent the 1807 Act, so in 1817 another Act of Parliament was passed which required all slaves to be registered. In 1823 more measures were passed by Parliament to ameliorate (improve) the conditions of slaves, but these were largely ignored by the legislatures and plantation owners in the colonies.

It had taken uprisings in the colonies and immense pressure from the well-to-do sections and elites of British society to achieve these goals. The attention of the anti-slavery campaigners now turned to the issue of full emancipation for slaves. They were up against a powerful foe in the plantation owners, who, with their allies in the corridors of power, were fighting a desperate rearguard action to preserve their wealth, privilege and power which was all predicated on slavery.

In 1824, the year that Aldridge, aged just 17, arrived in the UK, the Coventry Herald newspaper was proactively supporting calls for abolition. A long editorial piece of 30 January included:

This newspaper consistently opposed slavery. On 11 March 1825, it published a letter from a Coventry resident containing the text from a handbill that was being widely circulated elsewhere in a "distant part of the kingdom," and requesting that the Herald help spread its message. The handbill was a powerful indictment of slavery and called for a boycott of sugar imported from the Caribbean colonies. Part of it read:

On 18 November 1825, resolutions from a public meeting held at the County Hall on Thursday 16 November were published. The purpose of the meeting was to consider the best means of promoting the abolition of slavery.

In its edition of 3 February 1826, it reported that another meeting convened by the Mayor, James Weare, was held at the County Hall on 2 February, and petitions to both Houses of Parliament were left in the venue for signatures until the evening of Monday 6 February. The one to the House of Lords was presented by the Marquis of Hertford, who was the Recorder for Coventry, on 17 February. Its wording was related to the amelioration measures of 1823 being ignored.

Another editorial published on 26 May 1826 included:

It is sufficient for us to know that human beings are bought and sold by Englishmen as they traffic in sheep and oxen - that these poor creatures are controlled and scourged at the sport and gust of their masters - that the dearest ties that bind the hearts of mankind in unison are disregarded, in their case, and children and parents, and husband and wife, are separated, if it should suit the convenience of their buyers. It requires no effort of rhetoric to exhibit the heinousness of this system, so repulsive to our feelings.

How perverted that judgement must be that can see in it no crime, and how cold the heart in which it can excite no sorrow. A man may strike another, and take a few halfpence from his pocket, and be hanged; and another shall habitually have crowds of women and children severely beaten, and he shall daily rob them of the produce of their labour, and the world will do him worship and call him honourable.

To what base uses will not the love of gain induce mankind to resort! How it will distort the truth and deaden the feelings, and enable men to perpetrate the greatest crimes without pity or remorse.

In its edition of 23 February 1827, it heartily recommended that supporters of slavery read a pamphlet called "Common Sense on Colonial Slavery" which it said powerfully rebutted their arguments.

As the above illustrates, Coventry clearly had a well-established anti-slavery / abolitionist movement prior to the talented young actor first gracing the stage of its theatre. It was not unique in this - towns and cities across the United Kingdom (which then included the whole island of Ireland) had similar movements and the Houses of Parliament were deluged with petitions calling for an end to slavery.

* * *

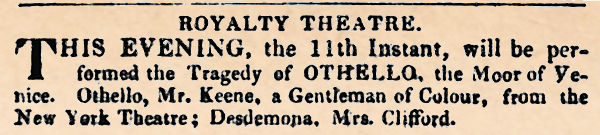

n 11 May 1825, Ira Aldridge, who was using the stage name Frederick William Keene at this time, made his theatrical debut in England. This was at the Royalty Theatre in the east end of London, where he went on to perform a number of times that month. The use of Keene as his surname was probably a nod to Edmund Kean, who was regarded as one of the greatest Shakespearian actors of that time.

n 11 May 1825, Ira Aldridge, who was using the stage name Frederick William Keene at this time, made his theatrical debut in England. This was at the Royalty Theatre in the east end of London, where he went on to perform a number of times that month. The use of Keene as his surname was probably a nod to Edmund Kean, who was regarded as one of the greatest Shakespearian actors of that time.

We know this from adverts and reviews published in the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser (London) newspaper. He initially played Othello, becoming the first Black actor to perform this role in the UK (see article, right), and went on to perform the role of the slave Gambia, in an operatic drama with an anti-slavery theme called The Slave. In October of that year he performed at the Coburg Theatre, also in the capital city, and this drew the attention of the wider London press. Their reviews - good and bad and often featuring racial prejudice and stereotypes - brought him to the attention of the wider public. One critical review loaded with racial prejudice sarcastically labelled him the "African Roscius". Rather than be offended, he appears to have "owned it" and from then on used it to successfully market himself.

An explanation of what this epithet meant is that the first part, African, was often applied in the British press to any person that they considered had African ancestry regardless of whether they were born in Africa or not. Roscius - whose full name was probably Quintus Roscius Gallus but who was known to posterity simply as Roscius - was a celebrated Roman actor noted for his portrayal of comic and tragic characters. His name was used as a mark of esteem for talented young actors in future generations. Some accounts suggest that Roscius had been born into slavery but was such a good actor that the dictator Sulla freed him from bondage and conferred on him a gold ring which was the emblem of equestrian rank. This rank conferred status and privilege.

Interestingly, The Taunton Courier, of 25 October 1826, in its 'CROWNSIDE' column reported that:

Peter Wilkins, stood indicted for stealing a gold ring, the property of F.W. Keene.

Prosecutor is a man of colour and goes about the country as a theatrical performer. On the 13th Sept. prosecutor was going in the skittle ground of a public-house at Axminster, kept by Shadrach Wilton, when prisoner came up to him familiarly and would insist on drinking with him, which prosecutor declined. Prisoner admired the ring on the prosecutor's finger, and would shake hands with him. In so doing, prisoner violently wrested from prosecutor's finger a ring worth about 2l. (£2)

Prisoner immediately jumped on his poney [sic] and rode off to Chard, where prosecutor found him at the Follett Arms; the prisoner first of all denied ever having seen the prosecutor or knowing anything about the ring, but on being closely searched he was observed to take it from his mouth and conceal it in his clothes, where it was found by the constable.

The prisoner, in his defence, attempted to prove that the prosecutor had sold the ring to him for five shillings; but the prisoner was found Guilty and sentenced to seven months' imprisonment.

After his performances in London, he then traversed the provinces honing his acting skills and building a name for himself. In January 1828 he was engaged as part of a company of players under the management of a Mr. Melmoth to perform at the theatres in Birmingham and Coventry.

An account of his first performance in Coventry, which took place on Monday 14 January, was given in the Coventry Herald of Friday 18 January:

It is with pleasure that we fulfil our duty in noticing the performances at the Theatre, which, since our last, have been maintained with a spirit highly creditable to the manager, and well worthy of the patronage of the public.

On Monday, was played the musical drama of The Slave, with the singular novelty of the part of Gambia by a performer, who is himself an African. We are willing to confess that our expectations were raised no higher, than to find the character presented with physical force, and with some boisterous declamation; and having no other clue to African theatrical capabilities, than what Mr. Mathews was pleased to give us in his "Trip to America," we were totally unprepared to meet with a performer, who could successfully challenge criticism, as to the intrinsic merits of his acting.

The African Roscius, as he is absurdly called, is above the middle size, with a figure somewhat national, but certainly not ungraceful; and he possesses a voice, which is, (with the exception of Macready's and Elliston's,) as fine, flexible, and manly, as any on the London stage. His action is unrestrained, and his knowledge of stage business and general effect that of a veteran. The conception of his part appeared accurate. The text was understood, and perfectly delivered, while there was great good sense and considerable discrimination of taste in its expression. We could perceive no foreign articulation, and were it not that the contour of his features and figure had plainly shewed the soil of which he is native, we could easily have supposed him an Englishman. Certain however it is, he has the intellectual susceptibility to feel the sentiments he utters, and professional skill to give them forcible expression. There were bursts of passion, especially in the celebrated part, where Gambia receives his emancipation, that were given with uncommon energy, and the deep tones of his grief in resigning his hopeless love of Zelinda, were as touching as they were manly.

We may be permitted to add, his model appeared to be Macready, and in this part it is perhaps impossible to find a better. Of course, the number of his characters is necessarily limited, yet, in Oronoko, (sic) Zanga, Selico in the Africans, and especially in Othello, a wide field is open for his exertions, and should he appear in town, as we are told he intends to do, as a stranger and foreigner we heartily wish him success.

To give context to the review it is worth explaining a little more about some of the people that are mentioned.

The Macready referred to was William Charles Macready (1793-1873) who was born in London and for a time educated at Rugby school. He performed at the Coventry theatre in 1825 playing Hamlet and Richard III. He is regarded as one of the greatest performers of Shakespeare's characters of that time and was used as a benchmark for others. He was a son of William Macready (1755-1829), an Irish actor, writer and theatre manager, who wrote a comic farce in two parts called The Irishman in London in 1792. This was also known as The Happy African and was primarily about the romantic relationships between Black and Irish servants. It was one of the plays performed on the historic day when the theatre opened in 1819.

Elliston was Robert William Elliston (1774-1831), who was another well regarded thespian and theatre manager. He had performed elsewhere in Coventry prior to the opening of the theatre in 1819, and then performed on its stage in the early 1820s. He then took on the lease for it in or around 1822 as well as holding the lease for other theatres including the prestigious Drury Lane in London. Along with his sons, he also owned or leased various properties in Leamington Spa, including its theatre where Aldridge would also perform in 1828.

Mr. Mathews was Charles Mathews, the leading comic actor and impressionist of that era. Mathews had visited America and based on his experiences created a show called A Trip to America. This lampooned those he allegedly encountered and included an over-the-top portrayal of what he claimed to have seen at the African Theatre in New York City, namely an African American actor reciting the famous "To be or not to be" soliloquy from Shakespeare's Hamlet. When the line that reads "And by opposing end them" is spoken, the audience interrupts and demands that a popular song called Opposum up a Gum Tree is sung, and it duly is.

This was all done for maximum comic effect so the words were bombastically spoken in pidgin English and played up to all the stereotypes of Africans and those of African ancestry which then existed in the British press.

Audiences apparently found this caricature of a Black actor 'butchering' Shakespeare hysterically funny. So clearly, like the writer of the review, some people would have turned up to the theatre expecting to see a similar performance from Aldridge if they had previously seen or heard about Mathews' offering.

Aldridge would himself later sing Opossum up a Gum Tree at Coventry and some adverts would intimate that he was in fact the actor that Mathews claimed to have seen in New York performing Hamlet and then singing that very song. This was not true and was a marketing gimmick. He probably went along with it at this time through pragmatism as it got punters through the door.

Aldridge performed in both cities until the early part of February. While he received praise for his performances, and had benefit performances in both theatres which may have earned him some extra money if they were well attended, the overall management of Mr. Melmoth, and the performances of some of the other actors came in for scathing criticism in the Coventry Herald. So clearly something had gone wrong after the initial praise Melmoth had received in the review published on 18 January.

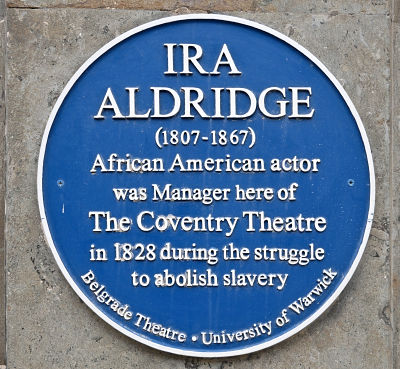

short time later, aged just 20, Aldridge himself became Manager of the theatre and in doing so made history - becoming the first Black person to ever manage a theatre in the United Kingdom. Whether he himself offered his services to those that owned or leased the theatre, or they approached him, I cannot say, but the decision makers clearly had faith in him and he eagerly threw himself into this new role.

short time later, aged just 20, Aldridge himself became Manager of the theatre and in doing so made history - becoming the first Black person to ever manage a theatre in the United Kingdom. Whether he himself offered his services to those that owned or leased the theatre, or they approached him, I cannot say, but the decision makers clearly had faith in him and he eagerly threw himself into this new role.

In an open letter to the people of Coventry dated 25 February, he pledged to tackle all the issues that occurred under Mr. Melmoth and take a much more professional approach to managing the theatre. The letter concluded with:

Expectations of him were clearly very high as this article in the Coventry Herald on 29 February 1828 demonstrates:

COVENTRY THEATRE - We have to announce that the Theatre will be reopened on Monday next, under the management of Mr. Keene, with whom the public is already acquainted.

The last performances were unsuccessful, owing, manifestly, to the actors being exceedingly bad. The new manager is aware of this, and has engaged an entirely new company, who will be, we have reason to expect, really respectable.

This is so essential to success, that it is useless to expect general support without it; at the same time, we feel assured, that if Mr. Keene can fulfil his promise, in giving the Theatre those attractions the public have a right to expect, he will be liberally rewarded for his efforts. The business of the late manager was conducted most negligently, as the public and his creditors are sufficiently aware. The pieces were frequently performed without a previous rehearsal, and the actors were consequently imperfect in the parts. We would recommend an invariable rule, of never attempting, under any circumstances, the performance of any piece, unless it had been carefully rehearsed; and we would also advise a strict infliction of all the penalties, which the laws of the Green Room impose on those imperfect in their characters. The public will pardon some degree of inability in an actor, but carelessness and indolence they punish with great severity on the manager, by declining to witness what is, in truth, an insult to the audience.

An advertisement in the same issue was printed giving details of the scheduled performances:

On 7 March, the same publication gave a brief but positive account of the opening performances under Aldridge's management:

COVENTRY THEATRE.

The Theatre opened on Monday, under the management of Mr. Keene. The business of the stage appears to be better conducted than by the last manager, and the company, as a whole, is decidedly improved. Those very estimable ladies, and excellent actresses, the Misses Penley, are engaged, and perform with more than their accustomed ability. On Monday night, Mr. Keene himself represented Othello, with considerable discrimination and effect. We regret that we are unable this week to notice the performances so fully as they merit.

After his performance as Othello mentioned above, it seems Aldridge only occasionally appeared on stage and concentrated on the management side of things. How long his time in charge lasted isn't precisely known but Bernth Lindfors in his excellent book, Ira Aldridge the early years 1807-1833, says it ended in May. However, by the end of the previous month - April - he was performing at the Theatre Royal in Worcester which is confirmed by an advert on page 3 of Berrow's Worcester Journal published on 24 April. The same book also quotes reviews from the Coventry Observer newspaper which suggest he was largely successful and had materially improved the theatre - the critic did have some issues with individual actors and the orchestra though. The Coventry Observer was published between 1827 and 1830 before it merged with the Coventry Herald. It is not available on the British Newspaper Archive website or in the Coventry Archives.

In June, Aldridge was back in the local area and performed at the theatre in Leamington Spa. A letter published in the Leamington Spa Courier on 23 August which was encouraging people to patronise the town's theatre included:

The exertions of the manager of our little theatre have been great. No endeavour has been spared to engage London performers, as stars; scarcely a week has passed, but one has visited us. The season commenced with Keen, (sic) the Black Roscius; and it is barely doing justice to him as an actor, to say he is clever, - in Othello, Zanga, Gambia etc., and such tragic characters as his complexion suits, he really is great. In Mungo, in the "Padlock," he is surpassed by no man in England.

It is believed that as well as portraying slaves in theatrical productions, he also spoke about the issue of slavery when he made the customary address to audiences at performances. These addresses, combined with his prodigious acting skills and management of the theatre is likely to have further galvanised the abolitionist movement in Coventry. This educated, articulate and talented young Black man confounded all the negative stereotypes and prejudice that the print media published about Africans and those of African heritage. In their eyes he would have been seen as living proof that the arguments of the slave owners were baseless lies.

The Coventry Herald of 16 May reported that petitions to both Houses of Parliament were available to sign at the County Hall in Cuckoo Lane. I haven't been able to find details of a meeting but one would presumably have taken place shortly before the petitions were left for signatures. On Thursday 22 May 1828, The Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry presented the petition to the House of Lords, "praying for the abolition of slavery," from the inhabitants of Coventry. On 9 June, Thomas Fyler, one of the two MPs for Coventry, presented the petition to the House of Commons calling for the same thing.

It isn't much of a stretch of the imagination to believe that the presence of Ira Aldridge in Coventry inspired the already active abolitionists to raise these further petitions against the vile practice of slavery.

As stated earlier, the Houses of Parliament were being deluged with petitions from towns and cities across the United Kingdom calling for the same thing and these continued right up until August 1833 when the Slavery Abolition Act received Royal Assent - another petition from Coventry was presented to the House of Lords on 29 July of that year. The Act took effect on 1 August 1834. However, even this did not mean the barbarism and cruelty was over. Most of the colonies moved to an apprenticeship system rather than full emancipation with full emancipation only taking place in Antigua. This was intended to be a transitional phase, which according to the plantation owners was to "prepare" slaves for their freedom. It was simply another ruse by them to maintain control and exploit the enslaved people, and was to all intents and purposes, a continuation of slavery. This system ended in 1838 when full emancipation finally took effect in all of the British colonies - the people of Coventry had sent another petition to parliament in that year to help ensure it happened.

As an aside, nobody should be under any illusion that this suddenly meant Black people achieved equality with white people and had the same rights as them in the Caribbean. Troubling Freedom by Natasha Lightfoot is an excellent book that looks at the island of Antigua in the aftermath of emancipation and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in this subject - it will open your eyes to the ongoing struggles and prejudice faced by the freedpeople of that island as they strived to achieve justice and improve their lives and communities against all the odds.

n February 1857, this time as a well-established actor and under his own name, Ira Aldridge performed again at the same theatre in Coventry, which was now known as the Theatre Royal. An advertisement for the theatre in the Coventry Standard newspaper of Friday 13 February included:

n February 1857, this time as a well-established actor and under his own name, Ira Aldridge performed again at the same theatre in Coventry, which was now known as the Theatre Royal. An advertisement for the theatre in the Coventry Standard newspaper of Friday 13 February included:

ROYAL,

ROYAL,Later that month, in the 27 February edition of the Coventry Herald, a review of the theatre included:

There have been several things deserving of notice during the week. In the first place, Mr. Ira Aldridge's delineation of Negro characteristics, in the "Padlock," on Friday last, was by far the most truthful we have ever seen, and would alone stamp him as a first-rate actor. Then, his Othello, repeated on Saturday, was a most finished performance, and showed the capacity for excellence of the most opposite kinds.

In late 1859, Ira Aldridge again performed at the theatre. A review in the Coventry Standard of 9 December read:

THE THEATRE

Miss Glynn completed her engagement on Friday evening (the 2nd instant), when the performances were for her benefit. The play was "the Winter's Tale," in which Miss Glynn personated Hermione with great effect.

During the present week, Mr. Ira Aldridge, the African tragedian has appeared on our boards. He is an actor of much power, his execution at times being equal to that of the greatest histrionic celebrities; but he frequently errs in conception ; and we do not like actors to alter the text of their author especially when that author is Shakespeare.

The play-going public are much indebted to Mr. Henry Powell, the enterprising manager, for affording them an opportunity of seeing dramatic "stars" of such magnitude as Miss Glynn and Mr. Aldridge.

The Coventry Herald and Observer, of 9 December, in its "Diary and Appointments for the ensuing week" column, included for Friday 9 December:

Benefit of Mr. Ira Aldridge, at the Theatre, at Half-past Seven. Pieces - "The Black Doctor;" and "The Virginian Mummy."

Just above this was:

Lecture on American Slavery, by Mr. W. Craft, an escaped Slave, at West-orchard Chapel, at Half-past Seven.

On page 4, the recent goings on at the theatre were reviewed in the "Local and District News" section. It began with:

The piece continued to effuse praise on Miss Glyn - who was presumably Isabella Glyn or Glynn - before returning to the star of the present week:

It is noticeable that the newspaper reviews did not make the connection with his first appearance in Coventry around 30 years earlier or his brief spell as manager of the theatre. Perhaps this was down to a turnover in staff in the intervening years or simply the fact that Aldridge went under the name F. W. Keene in 1828.

His time as manager was recalled in the Coventry Herald of 31 December & 1 January 1916. Its 'PLAYS AND PLAYERS' column included the following:

THE AFRICAN ROSCIUS & YOUNG ROSCIUS

In theatrical annals there is more than one player who adopted the name of the Grecian thespian, Roscius. The first Young Roscius, or Master Betty, of Shrewsbury, paid a visit to Coventry, or was announced to do so, and the magistrates prohibited him playing. That was during the sojourn of Mr. Stephen Kemble's company at St. Mary's Hall early in the nineteenth century. In 1828 the city received the African Roscius (F. W. Keene), and in 1830 another Young Roscius, W. R. Grossmith by name, of Reading, was here.

Again, the author of this piece has seemingly not made the connection that F. W. Keene was in fact the illustrious Ira Aldridge.

In August 2017, a Blue Plaque was unveiled in the Upper Precinct to commemorate the historic events of 1828. I remember seeing this on the local news on TV at the time. Prior to that, despite having a good broad general knowledge of local history, I can honestly say I knew nothing of Ira Aldridge or his incredible connection with Coventry. Those responsible deserve immense credit for making this happen. This of course was followed in 2021 with the stunning mural and amazing sculpture. You can also find a painting of Ira Aldridge among an interesting pastiche of Coventry history on the walls of the Coffee #1 shop in the Friargate One building near the railway station.

These are all fitting tributes that honour Ira Aldridge - a trailblazing actor and champion for equality and social justice.

* * *

side debate that the blue plaque has generated is that of what the theatre in Coventry was actually called. Some argue that it should read "Theatre Royal" and not "The Coventry Theatre". They are adamant it was the Theatre Royal and was always called this. They further argue that it causes confusion with a later Coventry Theatre located elsewhere.

side debate that the blue plaque has generated is that of what the theatre in Coventry was actually called. Some argue that it should read "Theatre Royal" and not "The Coventry Theatre". They are adamant it was the Theatre Royal and was always called this. They further argue that it causes confusion with a later Coventry Theatre located elsewhere.

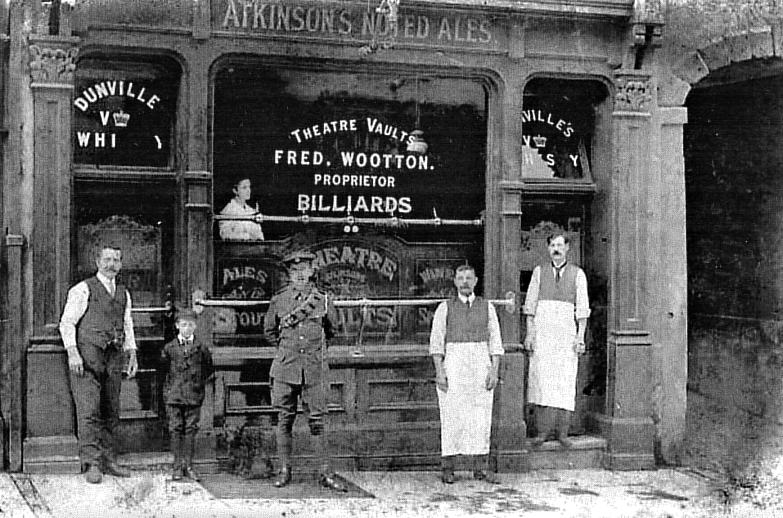

The theatre was erected by Sir Skears Rew, a former Mayor of Coventry, in the yard at the back of his house in Smithford Street. This yard was bounded at the other end by the Vicar Lane chapel, and not too far away was a military barracks. It opened on 12 April 1819 - Easter Monday - with a company from the Theatre Royal, Windsor led by Mr. Penley doing the honours. Some histories of the theatre mistakenly state that it opened in 1818. Penley also held the lease for the first few seasons before Mr. Elliston, who we have heard a little about previously, took it on.

In the 1820s, with the exception of two adverts in the summer of 1824 which do call it "Theatre Royal" and have the Royal crest too for good measure (9 July and 6 August, Coventry Herald), the theatre, both in Coventry and crucially elsewhere, was never referred to in newspapers as "Theatre Royal" or "Theatre Royal, Coventry". It is always "Theatre, Coventry" or "Coventry Theatre" and even its handbills, which were basically what we would nowadays call flyers, just said "Theatre, Coventry." In an advert in the Coventry Herald from 16 June 1820, it says "New Theatre, Coventry". When leases for it were advertised in London newspapers in this decade, one said "City of Coventry Theatre" (The British Press, 8 June 1822) and the other "Coventry Theatre" (The Morning Herald, 26 July 1828).

"Theatre Royal" became common in the late 1840s. I have found one advert from 1845, a couple from 1847 and then from 1848 onwards it became the norm for it to be called this. In November 1865, it became a music hall for a while and was usually advertised as "Theatre Royal Music Hall". This appears to have lasted until September 1868 when it reverted back to "Theatre Royal". It closed for good on Saturday 23 March 1889 and two days later, on Monday 25 March, its replacement, advertised at that time as "The New Royal Opera House," opened in Hales Street. In June 1889, the old Theatre Royal building became the "Empire Theatre of Varieties".

So, what is the story? 'Theatre Royal' was normally considered to be a prestigious title. It wasn't something you hid under a bushel. It was used by theatres that had received the 'Grant of Royal Letters Patent,' which gave them the right to stage 'legitimate drama' - legitimate meaning, for example, the plays of Shakespeare and serious operas. In theory at least, this prevented other venues nearby from putting on such productions. Other 'Patent Theatres' across the UK were not shy in advertising that they were a 'Theatre Royal'.

I don't doubt for one moment that Sir Skears Rew obtained such a grant, possibly in 1816. It would have been issued by either the Prince Regent - who had unexpectedly conferred a knighthood on the then Skears Rew, who was Mayor of Coventry, in November 1815 at Coombe Abbey - or from the Lord Chamberlain. This entitled him both to build the theatre and ensure it was able to stage the highest level of dramatic productions. I also think this patent would have been for an initial 21 years. During this time I'm assuming the patent meant that licensing of plays at a local level by the Mayor of Coventry or Magistrates, could be bypassed though I may be mistaken about this.

(In 1857, the Coventry Theatre Lessee Company took over the theatre. They were created

"for the purpose of purchasing the lease, grant and properties of the Theatre Royal Coventry and rearranging, enlarging and redecorating the same to hold it for operatic, dramatic and other purposes." The mention of grant in the blurb is reference to the original 'Grant of Royal Letters Patent' which every new proprietor would inherit.)

This would have been the logical thing for Rew to do - he was an astute businessman and this was a money-making venture. He was not a theatrical impresario. The new theatre had to be as commercially attractive as possible, as once completed, it was to be leased out, presumably to the highest bidder.

And it did indeed prove to be an attractive opportunity - the calibre of leaseholders, managers and actors that were involved with it in its first ten years are testament to that.

The first instance of local licensing for the theatre I can find is in 1837 (counting back 21 years got me to 1816) and it is always licensed locally after that. The Royal Patent was permanent and lasted until the theatre closed - regardless of the original 21 year term.

All this meant that the theatre in Coventry could therefore be styled as a 'Theatre Royal', but it didn't have to do this, and for some reason, this wouldn't happen until much later. Despite being a Knight, from what I've read about Sir Skears Rew, he might not have wanted the theatre called that. He died on 24 April 1828, aged 64 after a long illness. He lived in High Street at this time and not the house in front of the theatre. This was the same day that the Worcester Journal was advertising that Ira Aldridge was to shortly perform in Worcester. I did view a copy of his Will at the Coventry Archives to see if it mentioned the theatre. It did once, but just called it 'theatre'.

If Rew had instructed leaseholders not to call it 'Theatre Royal,' maybe this was gradually forgotten after his passing. King George IV (1820-1830) is said to have been an unpopular monarch. He was followed by William IV (1830-1837) who appears to have been more popular, and then came Queen Victoria (1837-1901) who the history books tell us was very popular indeed. Maybe it is no coincidence that the theatre became known almost exclusively as the 'Theatre Royal' during her reign and milk the Royal connection for all that it was worth?

Also, The Theatres Act of 1843 essentially broke the monopoly of 'Patent Theatres'. Other theatres and places of entertainment had been successfully circumventing the ban on them staging legitimate drama, and the way they did this had proved very popular with theatre goers. This act more or less acknowledged this, and that the system of licensing theatres needed an overhaul. Afterwards being a patent theatre carried less clout than before - leaving the Royal connection as the main advantage. It also meant much more competition at a local level.

While theatre critics in Coventry newspapers may have informally referred to it simply as 'the theatre' or 'theatre', which is understandable, as readers would have known they were talking about the only theatre in the city, it is baffling to me that advertisements, handbills and especially those adverts in the London press inviting tenders for the lease do not call it 'Theatre Royal' or 'Theatre Royal, Coventry' if that was indeed its actual name at this time.

So, in conclusion I personally don't have any issue with the wording on the blue plaque. In this period I would suggest it was called the 'Coventry Theatre' which was also a 'Theatre Royal'. Later, it was solely the 'Theatre Royal' in official advertisements apart from a few years when it was the 'Theatre Royal Music Hall'. It's not worth losing any sleep over to be honest, but if anyone can track down the original patent details please do so and get in touch - it would be interesting to know what it actually says. The same goes for other examples in the 1820s of the theatre being called 'Theatre Royal, Coventry'.

Further reading, viewing and acknowledgements:

Ira Aldridge was incredibly popular in Ireland and there is a great video about him by the eminent Irish historian Christine Kinealy in conjunction with the Irish Heritage Trust, which not only details his time in the emerald isle, but also tells the story of what is known about his early life and the challenges that he faced. It is well worth watching and can be viewed here:

In terms of books, as mentioned earlier, Ira Aldridge the early years 1807-1833 by Bernth Lindfors, first published in 2011, is meticulously researched and a very good read. It includes a chapter about his remarkable time in Coventry.

The online British Newspaper Archive has once again been of invaluable assistance to my own research. I would warn any readers that the racial prejudice contained in the old newspapers is eye wateringly bad, so please be aware of this if you do your own searches on F. W. Keene or Ira Aldridge.

Thank you also to the staff at Coventry Archives located in The Herbert. Although I didn't really discover anything new from my visits, their courtesy, assistance and professionalism is a credit to them.

And, of course, thank you to Rob Orland for arranging & publishing on this website.

Simon Shaw, 2024

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026