|

Index...

|

t's 2022, and the approaching 82nd anniversary of the Coventry Blitz got me thinking of when Coventry commemorated its 50th year in 1990. I was still working at the Transport Museum, which had been open for ten years. The Managing Director of the Museum, Barry Littlewood, was seconded to manage the city's 50th year Commemoration of the Coventry Blitz, with Peace and Reconciliation as its main theme, but he would be away for all or most of 1990. The city council and Lord Mayor wanted a big event because the special guest was going to be the Queen Mother, who had visited Coventry with the King on his second visit to the city and the cathedral. The Lord Mayor was excited and wanted everyone to get involved.

t's 2022, and the approaching 82nd anniversary of the Coventry Blitz got me thinking of when Coventry commemorated its 50th year in 1990. I was still working at the Transport Museum, which had been open for ten years. The Managing Director of the Museum, Barry Littlewood, was seconded to manage the city's 50th year Commemoration of the Coventry Blitz, with Peace and Reconciliation as its main theme, but he would be away for all or most of 1990. The city council and Lord Mayor wanted a big event because the special guest was going to be the Queen Mother, who had visited Coventry with the King on his second visit to the city and the cathedral. The Lord Mayor was excited and wanted everyone to get involved.

Various plans were drawn up and the citizens of Coventry were all invited. Besides processions and a big service in the New Cathedral there was going to be a new Peace Garden next to Nelson Mandela House, Bayley Lane (the garden is now gone), which was going to be opened by the Queen Mother.

Drapers Hall was intended to be made into a Blitz Museum - visitors would go into the building through the main tall doors, and into the first room where they would be welcomed by people in costume, tin helmets and gas masks. After introductions a Air Raid Warden would quickly take them down in to the basement when the 'air raid siren' sounded. (In the basement there are still original Second World War posters on the walls of a large kitchen and other rooms.) On the sound of the 'all clear' they would be brought up a different flight of stairs into another room that looked like it had been bombed, where they would be told what had happened on the night of the 14th and 15th November 1940. Finally, they would be taken into the bunting-covered main hall, where they would see people celebrating the end of the war and Winston Churchill on the balcony giving a speech.

For this to work the city council would supply the building (Drapers Hall) and a one-off amount of funding, but the rest of the money had to be raised by sponsorship and run by an exhibition agent. There were a few large manufacturers in the city who were interested, but none would supply the complete funds, so it failed and there would be no blitz exhibition. This sad news was announced around September - only about ten weeks until the event.

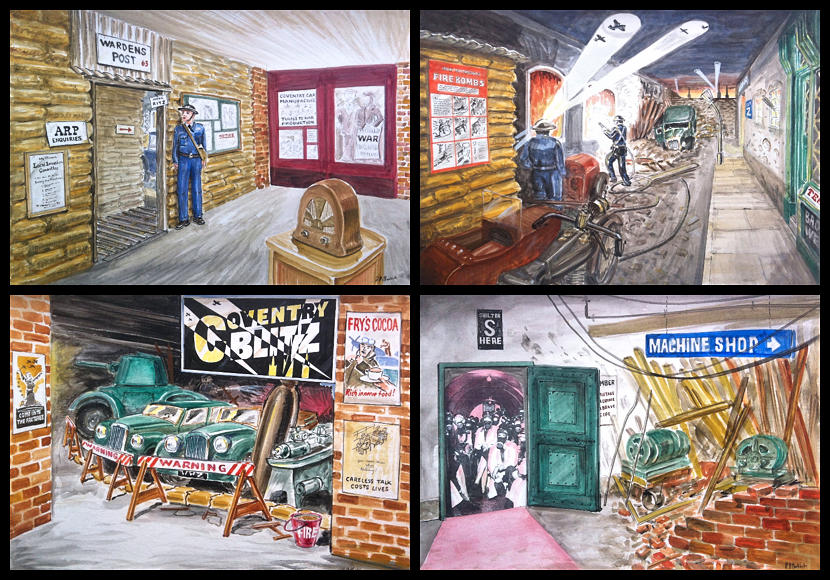

I suggested to Barry Littlewood that a "Blitz Experience" could be built inside the Transport Museum. I'd already had various street-scenes built from the turn of the century, with shops, hotel, post office and garage in the museum. I did some illustrations (below) and explained how the story-line could run - that the bombing was not just to attack the city, but to knock out Coventry's industry, which was producing military goods in one-time car and cycle factories that were everywhere in the city and concentrated in the centre. This would fit in with the story of the growth of road transport manufacture in Coventry. Barry liked the idea and gave his support for it to be in the Transport Museum, and he was able to get the city council and Lord Mayor to agree to us having the funding that would have gone to the Draper's Hall project.

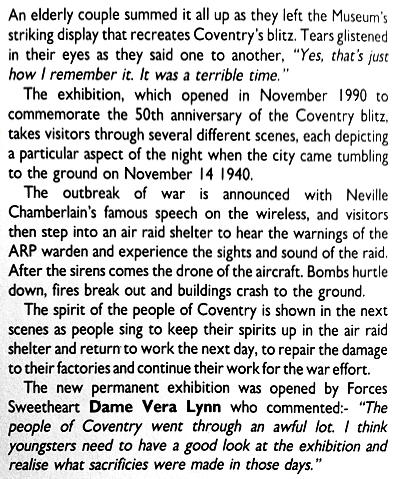

The Blitz Experience was to be staffed with a museum assistant, who would lead people through the displays. First Neville Chamberlain was on the radio, and the British Prime Minister was announcing that Britain was now at War with Germany. I was able to install a projector into the desk that the radio was on, projecting photographs onto the rear wall of Coventry factories changing from car production to plane and gun manufacture.

A museum assistant would act the role of ARP warden and take visitors through the Bomb Shelter into a street that was under attack, with the aid of sound, smells, flashing lights creating the effect of fire, and a smoke machine. Beams of light were scanning the sky to the sound of firemen putting out fires that were crackling until the 'all clear' siren sounded. A running commentary would explain what happened. Visitors were then led into a bombed-out factory, but all the staff were safe - just coming out of the bomb shelters to help clear up.

But first a unexploded bomb had to be disarmed, which had come through the roof and landed in the workshop. This 1,000 pound bomb (nicknamed Herman due to its large size!) had originally landed on the Humber factory in Humber Road, and after all of its explosive had been steamed out they put it in the Managing Director's office where it stayed for the rest of the war.

e were given the go-ahead but we did not have much time. We hired some bricklayers and a carpenter and set about making it. I got a free telephone-box from the GPO when I told them what I was doing, and the bricks came from the old railway stable-block, now the site of the Central Six Retail Park. The burnt timbers I got from the old Jesmond Road Baptist Church, which had been in a fire. At the time it was not being used as a church, which had moved to a new building - it had become an Asian community centre. They were very surprised when I turned up and asked if I could have their burnt timbers!

e were given the go-ahead but we did not have much time. We hired some bricklayers and a carpenter and set about making it. I got a free telephone-box from the GPO when I told them what I was doing, and the bricks came from the old railway stable-block, now the site of the Central Six Retail Park. The burnt timbers I got from the old Jesmond Road Baptist Church, which had been in a fire. At the time it was not being used as a church, which had moved to a new building - it had become an Asian community centre. They were very surprised when I turned up and asked if I could have their burnt timbers!

The old lathe came from a scrapyard, who gave it to me for free after I told them what I wanted it for. That scrapyard was where the Ricoh Arena is now. It was surprising how people would give things when asked. All the corrugated steel came from an old garage in Green Lane, on the understanding that we knocked it down and took it away ourselves. The more professional effects, like lighting and sound, we were able to get the Belgrade Theatre technical staff to do, which they mainly did in the evenings to fit around with their Theatre work. We worked on it day and night, and I even took my son and daughter into work while my wife was working as a nurse on nights. My kids loved it, as I would get them to throw mud and dirt up the walls that I had just painted to give that exploded factory look. We all mucked in filling sandbags, etc.

For the opening, on 14th November 1990, we got Field Marshal Montgomery's staff car out of the collection and picked up Vera Lynn and her husband from the station. Alan Titchmarsh joined them and they were all delivered to the entrance of the Museum in St. Agnes Lane.

Vera Lynn officially opened the exhibition. I showed her through the Blitz Experience and she was very interested. After she had seen the exhibition she was shown into the main hall of the museum, where amongst fire engines and buses sat many tables of Coventry people, who had been in Coventry on the night of November 14th 1940, having tea. My mum was amongst them, having been only 16 at the time of the blitz, living in Siddeley Avenue, only a stone's throw from the Humber Factory. The BBC TV outside broadcast team were there for the morning show presented by Alan Titchmarsh. He chatted to Vera and various survivors of the Coventry Blitz. After the show many veterans were shown around the Blitz Experience. I went through with my mum and some of the other ladies whom she had got to know, but when we came out of the exhibition most were crying, as it had brought it all back to them. This was very upsetting and the last thing I had expected, which made me feel very humble.

The Blitz Experience exhibition is still there, but has been altered a bit over the years, and because it is a set of different tableaux, you have to stop, watch and listen to each one. But without a museum guide stopping visitors from just walking straight through the street scenes, most of them do not get the full effect and story.

Later on that day, the 50th year Blitz Commemoration continued with the Queen Mother going to the Council House to meet the Lord Mayor. After her visit they then walked to the 'Peace Garden' in Bayley Lane, talking to people on the way. They then carried on to the old Cathedral, where there were many old Coventrians who were greeted by the Queen Mother. This was very much appreciated by the citizens of Coventry, and they remembered that when Buckingham Palace was bombed she famously remarked that now she could look the East End in the face. She was tireless, as was the King, in visiting the bombed cities of Coventry, Plymouth, Bristol, Swansea, Liverpool, and many others, as well as wandering through the debris in the streets of London. She never failed to bring cheer to the homeless, desolate, and bereaved. The Royal party carried on into the New Cathedral for a special service with many overseas visitors.

That evening there was a ring of thousands of people around the city centre with torches, and they were all pointed up into the air for the two-minute silence. After a parade led by the Lord Mayor and Vera Lynn in Monty's staff car, they got out of the car and mounted an action platform under the tent at Cathedral Lanes, which was, I think, only just opened that day. The Lord Mayor, Councillor William Arthur Hardy, gave the salute along with different groups of old Soldiers, Firemen, Police, Ambulance and First Aid organisations, Veterans, Scouts, Nurses, various bands, plus lorry loads of different floats with blitz themes. A special show of laser-beams and moving projected images were displayed on various buildings in Broadgate, with music and commentary telling the story of the run-up and events of the Blitz, and finishing with the logo of the Dove of Peace and the Three Spires, with the Peace and Reconciliation message. This light show was such a success it was shown again for the next two nights - each time getting hundreds of people attending. The evening closed with Vera Lynn singing a medley of wartime songs and getting the people of Coventry and all of crowded Broadgate to sing along. Most of the day was covered by the national TV and press. It does not feel like 32 years ago that Coventry really pushed the boat out for this commemoration.

Paul Maddocks, 2022

Paul's next excellent Transport Museum article tells us how Coventry's Land Speed Record Cars got here.

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026