|

Index...

|

rom an early age, John Edward Clarke became fascinated with an enchanting ruin standing just 100 yards from where he grew up. Caludon Castle, once a grand fortified residence in Wyken, was to become John's passion for the nest 60 years. His inquisitive mind eventually led to a career in journalism, before going on to set up Coventry's first PR agency, and even become a Chairman of Coventry City F.C. In 2005 John was awarded the OBE for Services to the community of Coventry.

rom an early age, John Edward Clarke became fascinated with an enchanting ruin standing just 100 yards from where he grew up. Caludon Castle, once a grand fortified residence in Wyken, was to become John's passion for the nest 60 years. His inquisitive mind eventually led to a career in journalism, before going on to set up Coventry's first PR agency, and even become a Chairman of Coventry City F.C. In 2005 John was awarded the OBE for Services to the community of Coventry.

In 2013 many years of persistence and research finally paid off. Ably assisted by George Demidowicz and Stephen Johnson, John was able to produce a luxurious book; A History of Caludon Castle - the Lords of the Manor of Caludon, and, in 2024, a 44 minute documentary, available on YouTube. John has generously allowed me to publish here his favourite section of the book - Chapter 4: Life at Caludon with the Berkeleys, 1592-1605.

ith the almost complete demolition of the buildings on and around the moat at Caludon Castle in the mid eighteenth century, it has proved difficult to reconstruct their appearance. The drawings by Pete Urmston of Caludon based on the ground plan discovered by the geophysical surveys, however, provide a good impression of how the castle may have looked in the third quarter of the sixteenth century (Fig 1). By contrast, for the period around the turn of the seventeenth century, after the Berkeleys had radically rebuilt and refurbished Caludon, one of their favourite residences, there is abundant evidence of day-to-day life and events at the castle. Accounts have come to light that provide much detail on the running of the household and the management of the estate, but this book-keeping has produced more than a meticulous financial record. Many aspects of the Berkeleys' personal life are revealed by the items and services that they purchased.

ith the almost complete demolition of the buildings on and around the moat at Caludon Castle in the mid eighteenth century, it has proved difficult to reconstruct their appearance. The drawings by Pete Urmston of Caludon based on the ground plan discovered by the geophysical surveys, however, provide a good impression of how the castle may have looked in the third quarter of the sixteenth century (Fig 1). By contrast, for the period around the turn of the seventeenth century, after the Berkeleys had radically rebuilt and refurbished Caludon, one of their favourite residences, there is abundant evidence of day-to-day life and events at the castle. Accounts have come to light that provide much detail on the running of the household and the management of the estate, but this book-keeping has produced more than a meticulous financial record. Many aspects of the Berkeleys' personal life are revealed by the items and services that they purchased.

The Berkeley family expenditure on luxury items is not unexpected, but we also discover that outgoings included charitable donations. Henry Berkeley was known for his profligacy, experienced by many as generosity, inspiring both loyalty and affection in those who benefitted. Smyth himself drew attention to Henry's local charitable gifts.

Each pauper received:

Smyth estimated that Henry paid out between eight and ten shillings a day from his own purse 'for private Almes' in small coins in addition to the food relief. On Maundy Thursdays 'many poore men and women were clothed by the liberality of this lord and his first wife [Katherine].' Over twenty pounds was given at Christmas, Easter and Whitsun.

The household expenses reveal that the ad hoc, daily relief was also distributed at the castle gates. In March 1595 a 'lame boy' was given 4d, along with '2 poore men at your Lords gates.'4 These acts of 'noblesse oblige' appear generous when seen in isolation and the recipients were undoubtedly grateful for them, the difference often between life and death for a pauper at this time. Many of Berkeley's peers in fact did not share his sense of obligation and were oblivious or indifferent to the poverty of their tenants. A note of caution must, however, be sounded for when the amount of charitable donations is compared with other items of expenditure in the accounts, the generosity does not appear to be so impressive. At Easter 1593, 39s was donated to the local poor 'at the gate'. In May 1593, 19s 9d was paid for 'Reynishe wine' and in the following February, 35s for a pair of pink silk stockings. In January 1595 Berkeley paid out 36s 6d for 'white whine for my lady' and in August, 43s for crimson velvet and another 43s 8d for green velvet to repair two chairs. In January 1597, £20 was given as a down payment for a new coach.

Not unexpectedly, a major category of expenditure was paid for the Berkeleys' personal items and belongings such as wearing apparel and furniture and the cloth required for it: a hose and doublet made for 'Master' [Thomas ] Berkeley cost 6s 9d, (March 1595), '1 oz and 1 quarter of black fatten silk' was needed to make a pair of 'backhose' (2s 6d), '13 yardes and a half of bone lace' was required for '6 bandes', which together with six pairs of cuffs cost 19s 6d (May 1595). Expensive cloth was also used in upholstery and decorating bedding: In July 1595 Humfrey Kindon made a down bed, which consumed '24 yards of white fustian cloth at 3s 2d a yard', '3 dosen of blewe and white binding lace to mend the bed (18d)' and 'Crimsen and White silke laces to lace the seames of the bed' (15s 3d). In the following month '18oz of Crimsen silk and gould fringe at 5s the oz' was used to decorate chairs, totalling £4 12s 6d. These expensive items, beyond the financial reach of the servants and workmen who toiled at Caludon, convey an impression of the sumptuousness of the décor and fittings in the castle. There were at least two Arras tapestries, one in the hall and the other in 'my Ladies [Katherine's] chamber.'6 These needed to be cleaned and repaired (April, July 1596). A painter was paid 12d for 'laying coulers [colours] in the great chamber,' (Jan 1594). The rich fabrics of the Berkeleys' dress matched this luxurious environment. Other expenditure extended the display of opulent colour and texture into the garden, with the extra cache of rarity and curiosity. Three peacocks cost 4s 6d in November 1595.

We also catch a glimpse of the Berkeleys' more personal possessions, some of which they may have valued amidst a surfeit of luxury: Henry's watch was mended for 9s (Aug 1595), his two crossbows provided with new strings, arrows and bolts (1s 8d) and a looking glass purchased for 2s (July 1595). After Lady Katherine died in 1596 a bill was settled with 'Tuck the gouldesmith for two ringes sett in my Ladies time' (June 1597).

The accounts also record the more mundane purchases that the running of a noble family's household required. These included a new cart (wayne) with its fittings (25s 6d, Aug 1595), locks for doors to Master [Thomas] Berkeley's study (8d, March 1595) and the schoolhouse (6d, Aug 1596). 100 loads of 'stone Cole', each costing 3s, were delivered in May 1595, presumably from the local coal pits, but despite their geographical proximity this was still expensive fuel in the late sixteenth century (£17 20d). Charcoal was, however, even more expensive at 14s a load and only three loads were supplied, perhaps to heat braziers.

The Caludon accounts are comprehensive, listing items of expenditure in a wide variety of categories including payments to hired workers. These provide an insight into the comparative cost of labour and service in the late Tudor and early Stuart period. For example, in February 1594 a barber was paid 2s 6d for cutting Henry Berkeley's hair and, by contrast, Thomas Truelove and Henry Bushell were paid 2s for two days 'threshing in Calowdon Barne.' The sum of 6d a day was apparently the 'going rate' for basic labouring, for 2s was received by Thomas Newcom for '4 daies ditching the hoppyard,' (April 1595).The 'goodwife Ascue' was paid a shilling week for seven weeks for the unpleasant task of emptying the closet stool (toilet) (May 1604). The more skilled work of William Howe, a carpenter, was rewarded with 4s 6d for five days work making a cheese press at Henley (June 1595). At the top of the craftsman's scale Humfrey Kindon was paid 16s 6d for 'dressing Mr Berkeleys rapier,' (Sept 1595). It is evident that Caludon in its heyday was an economic magnet, providing work for local people at all levels of skill. Tradesmen from the immediate parishes and further afield in Coventry supplied the house with all manner of goods, from food, medicines, barrels, locks, coal and fabric. The death of Henry Berkeley in 1613, and the subsequent departure of the remainder of his family must have severely affected the livelihoods of the local population that had come to rely on Caludon for part or possibly all of their income.

The accounts record payments made to repair and maintain the Caludon buildings and for work done outside in the courts and fields. Through them we obtain a selective list of the rooms and buildings that were in existence not long after the Berkeleys had substantially rebuilt and renovated them. Some idea of the appearance of the interiors can also be gained. It is clear that the maintenance of the freshly restored Caludon buildings was still a major drain on resources, demonstrating how difficult it would have been for the succeeding grazier-tenants to continue this level of expenditure.

Much of the work was done by local craftsmen. In January 1594/5 John Sarge[n]son, a well-known Coventry mason repaired the stairs that led to the great chamber (6 days, 6s 6d) for which '40 foote' of stone was consumed (Fig 3). In June 1593 a painter mended the walls and pasted them with paper in Master [Thomas] Berkeley's study. The Arras tapestries in both the hall and in Katherine's chamber were dressed about the time of her funeral (April and June 1596). The hall tapestry was taken down, re-lined with canvas and re-hung on tenter hooks. Even though glass was expensive, a modernised house of the size of Caludon would be expected to have a goodly number of glazed windows. In July 1596 Hoskins, the glazier, scoured and mended the glass windows about the house.

Moving from works of art and craftsmanship to the disposal of human waste, Henry's 'Closet stole' (WC) was mended for two shillings in June 1595. It is tempting to think that the reference to a sweep cleaning out the chimneys in April 1593 included the one that survives in the present ruined wall. The existence of an armoury is known from the lamp black and oil which was purchased to maintain its contents. This room may have been in the main part of the house or in a separate building.

Frustratingly there was relatively little work done to the family apartments, perhaps because of their recent refurbishment and most items related to the service buildings. January 1595/6 was a busy time:

| To William Howe Carpenter for 3 daies work in setting the bellowes and setting his Anfield [Anvil] and other things | ................................ | 3s 4d |

| To Thomas Truelove, Thomas Astyn and Henry Buswell for painting the Smithy House | ................................ | 4s 6d |

| To Robert Seabridge Tiler for 3 daies in the sealing the Clock House with lathes and heare [hair] mortar at 1d the day | ................................ | 2 6d |

| To William Howe Carpenter for 5 dayes work in making needful thinges in the kitchen and mending the wheele Barrowes at 10d | ................................ | 4s 2d |

| to William Coxe Carpenter for mending of the plump [pump] | ................................ | 2s |

| To Robert Eliot mason for mending the kitchin and squilery [scullery] paving and for mending of ovens for 5 daies at 12d | ................................ | 5s |

| To Thomas Truelove, Thomas Astin Henry Buswell for 8 daies worke in the paling the woodyard | ................................ | 4s |

| more to them for 10 daies worke in paling of the great garden | ................................ | 5s |

| To William Howe Carpenter for one daies worke in the mending of the manger and work in the strawe house | ................................ | 10d |

Another important service room which required considerable work was the brew house. It appears to have been located near the bridge (April 1605). In May 1593 Thomas Cheyney, a cooper, made five hoops for the great mash vat (20s). This was followed in May 1595 by more coopery:

| Paid the Cowper for 3 great hoopes for the great ycking [sic] fatt [vat] | ...................... | 24s |

| for 8 hoopes for a mashe fate [vat] | ...................... | 32s |

| for settinge in 3 new staves in the mashing fate [vat] | ...................... | 10d |

| for 3 hoppes for the long Coler in the slaughterhouse | ...................... | 3s |

Other service buildings in which repairs were carried out included: the pigeon house, laundry and tallow store house (June 1593), straw house (January 1593/4), candle house and bakehouse (Dec 1595), dairy house, barn and granary (July 1596) the keepers lodge and schoolhouse (Aug 1596).

There is information on the spaces and courtyards, which were either situated around the main building complex on the moated platform or outside of the moat. There are several mentions of gardens, including the 'great garden', which was fenced in January 1594/5, an 'Upper garden' and an 'old garden' (Aug 1596). If any of these were located on the moat, they would most likely have been on the west side, between the hall and chamber ranges and west arm of the moat water. Here seclusion from the busy main courtyard entered from the gatehouse on east could be guaranteed and is the location chosen for the bird's-eye view (Fig 4). Next to the pigeon house was a courtyard fenced with palings in June 1593. There was a hop yard, essential to keep the brewery supplied, but location unknown. In June 1593 it was 'dressed', and in April 1595 - ditched. The moat itself received some attention with posts and rails constructed around the internal circuit (Oct 1595). Steps were cut into the bank, probably on the north side in order to reach a boat and cross to the banqueting house (Nov 1595). Close by a number of new channels were dug in the same month to avoid the pool overflowing.

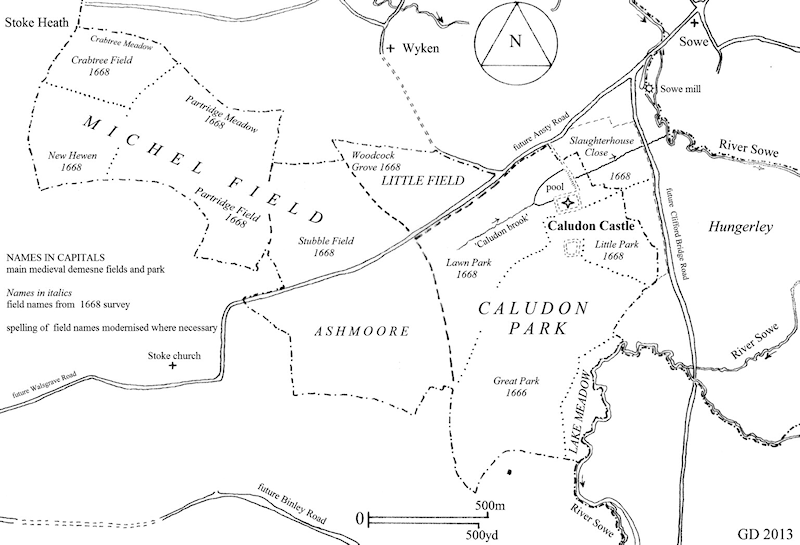

The accounts record work done farther afield on the demesne and in the park. The park was railed in July 1595 and the same workmen were transferred to mow Lake Meadow and Hungerlie Meadow. Further mowing took place in the same month on Stokehoke [Stoke Hook], Ashmore meadow and Slaughterhouse Close (Fig 2). The carpenter, William Howe, erected more park paling and mended all the gates. The mown hay was then gathered into ricks and by the following November the hayricks were fenced. In the same month a rabbit warren in the park was secured by erecting a 'new haye (fenced enclosure) for coneys' to prevent their escape. Rabbit meat was an important source of protein along with fish from the pool; a casting net was made in June 1593.

he Caludon household, consisting mainly of servants and retainers, was extensive and hierarchically organised, a necessary display of aristocratic status. The more servants that could be maintained and the greater their differentiation, the higher was the prestige that the family enjoyed, despite the huge expenditure required. The Berkeleys were no exception and the costs of running their household contributed to their disastrous financial situation and the Caludon accounts are illuminating in this respect.

he Caludon household, consisting mainly of servants and retainers, was extensive and hierarchically organised, a necessary display of aristocratic status. The more servants that could be maintained and the greater their differentiation, the higher was the prestige that the family enjoyed, despite the huge expenditure required. The Berkeleys were no exception and the costs of running their household contributed to their disastrous financial situation and the Caludon accounts are illuminating in this respect.

At the top of the pecking order stood the household steward. He was the principal administrator and it is thanks to the preservation of his records that this chapter has been written. The steward did not compile the accounts, however; this was left to a clerk or 'receiver', whose clear hand appears throughout the full run of accounts from 1592 to 1605. The steward's position was crucial and one which required a man of both great diplomatic and bureaucratic skill, and, above all, trustworthiness. Henry Berkeley was blessed with the intelligent, perspicacious and loyal John Smyth, who was his household steward from the death of Katherine in April 1596 to the arrival of John Creswell about a year later. John Smyth then took up the apparently more lucrative office of steward of the Hundred and Liberty of Berkeley. He remembered:

Creswell could not have savoured dealing with the potential insubordination or misbehaviour of staff serving Henry in his favourite pursuits, feasting and hunting, but he was paid a handsome wage as recompense. In October 1604 the steward received £10 for half a year, making his annual salary £20, a substantial sum. A half-year payment to John Smyth appears below Creswell's in the account, but for significantly less - 33s 4d. By this time Smyth was also acting as the family solicitor, 'preparing cases... and expediting the administration of the numerous Berkeley lawsuits.'9 He may have been paid from separate accounts for these duties, which had burgeoned and left little time to devote to the Vale of Berkeley estates.

It is probable that the steward would have lived at Caludon and maintained his office or 'counting house' there, for this was where the household resided for much of this period. Next below in the household hierarchy was normally the gentleman usher, who dealt with the day-to-day running of the household, organising the staff and dealing with visitors and guests. His role would have combined that of secretary, butler, and confidant and he was likely to have been on fairly intimate terms with Lord Henry. In 1604 a John Wheeler occupied this position for which he was paid the same as John Smyth - 33s 4d. Their names and that of John Creswell were prefixed by 'Mr,' denoting their status as gentlemen or squires, an important social distinction.

If rank is judged by the level of wages alone, however, then John Wheeler's position was more ambiguous, as there were other officials at Caludon who were more highly paid. An example was the position of 'Clerk of the Kitchen', occupied by John Prowting, who received 40s per half year, compared to Mr John Wheeler's - 33s 4d. He would have been responsible for maintaining the kitchen accounts and overseeing deliveries, leaving the cook, Hugh Fowler, who was paid even more - £3 6s 8d per half year, to concentrate on running the kitchen and deciding menus. This level of payment reflects the value that was placed on his work by Henry Berkeley. It is ironic that Henry was to die of food poisoning, but in the pre-ice house and fridge age this was an unavoidable occurrence. Another office of comparable status was held by John Freeman, who was Yeoman of the Horse. He received no payment 'because he hath a ground in Gloucester for his wages', presumably given to him by the Berkeleys. The keeping of the stables was an important and onerous duty, with horses needed in particular for Henry's other favourite pastime, hunting. Veterinary science was in its infancy, hence the administering of two 'drinks' of unknown fluid to a bay horse named 'Harry', perhaps Henry's favourite hunting horse and the bleeding of eighteen horses for 3s (May 1595). It is interesting that John Watson, the brewer, was paid the same as the gentleman usher, John Wheeler. Ale with its alcohol content, although weak, was valued as much for its lack of contaminants as for its intoxicating effects.

Humfrey Ellis was yeoman of the great chamber at Caludon and paid 40s, equal to the brewer and the clerk of the kitchen and more than the gentleman usher. The great chamber, presumably located in the main chamber range of which the ruin is a fragment, was distinguished from the 'lords chamber', a more private room, which was overseen by the groom, Robert Kinge (26s 8d). He would look after Henry Berkeley, brush and clean his clothes and generally be in his attendance whilst Henry was in occupation of his private apartment. The salary of Thomas Pinkerman, the falconer, set at 40s, reflected Henry's enduring passion for hunting at Caludon and farther afield. The list of staff given in October 1604 concluded with the following men and their half yearly wages:

| Ralph Heath, for his wages and bord for keeping Callowdon House | ................................ | £3 10s |

| Roger Segar, keeper of Callowdon Parke | ................................ | 26s 8s |

| Richard Cole, Usher and Slaughterman | ................................ | 26s 8d |

| John Borlson, Cator [caterer] | ................................ | 26s 8d |

| Barnaby Knott, footman for 1 quarter | ................................ | 20s |

| Thomas Stratton | ................................ | [no information] |

| John Burnell | ................................ | [no information] |

| The groome of the kitchin, for 1 quarter | ................................ | 7s 6d |

| The keeper's boy | ................................ | 10s |

It is interesting that there is a Keeper of both Caludon House, as it was called at the time, and a Keeper of Caludon Park. It is likely that Ralph Heath was responsible for the repair and maintenance of the main house in the same way that Roger Segar looked after the park, ensuring that its encircling pale was kept secure, timber and brushwood felled and transported away, the deer protected from poachers and hunting parties organised. Richard Cole was both an usher and a slaughter man, the latter duty taking time only when venison was needed for the Lord's Table.

It is difficult to estimate the size of Henry Berkeley's household from these accounts, as the great majority of servants were not formally waged, receiving board and lodging and other allowances in kind. These included grooms, resident farriers, huntsmen and porters as well as numerous footmen, postillians, kitchen and scullery maids, under-cooks and attendants. Many years earlier in the 1560s when Henry and Katherine travelled between Caludon, London and Berkeley, they were seldom attended by fewer that one hundred and fifty servants:

Henry's household was likely to have been much smaller, once he became a widower in 1596. The badges marked the servants with the Berkeley insignia. This was regarded by the family as essential to reflect their wealth and high status, but the marking was also as a means by which the servants could distinguish between themselves in their own rigid 'downstairs' hierarchy. In May 1595 'Harrison's wife' was paid £9 10s for:

| gentlemens badges 10 at 5s | ................................ | 50s |

| yeomans badges 20 at 4s | ................................ | £5 |

| gromes badges 12 at 3s 4d | ................................ | 40s |

The forty-two badges which were made could be interpreted as the number of servants in each of the Caludon ranks, but there is a possibility that an extra number was ordered for future use.

The duties of each of the servant offices were strictly defined, including the behaviour that was expected. Smyth, fortunately, provided a copy of the extensive rules of conduct. These had been compiled with the help of previous household stewards and other officers and approved by Henry and Katherine. It begins with the rules for the gentlemen. For example, no gentlemen should 'come into the great chamber without his cloake or livery coate'. They could not be absent from mealtimes without permission and when called to the dresser (presumably to serve food) they should 'behave themselves decently without noise or uncivill behaviour.' When the gentlemen rode out on any journey they were arranged in pairs ahead of Henry Berkeley and had to avoid 'lewd speech or other rudeness.'

The yeomen likewise were required to attend in the hall at all times, such as meals, and could not be absent without licence. They could not 'lye out any night' and had to be in their lodgings by nine o'clock. They had no right to enter the buttery, pantry, cellar, kitchen or scullery without good cause. These rooms would have been situated at the opposite end of the hall to the great chamber and were full of tempting provisions and goods. There appears to have been a separate dining chamber for the yeomen who were required to:

ortunately the accounts record not only the purchase of material objects, but also indirectly reveal the events which took place within the walls of Caludon, given an invaluable additional perspective by Smyth. The Berkeleys were hospitable, known for lavish entertainments at which music, singing and dancing, as well as acting, played an important part. They shared their pleasures with their guests, invited, depending on the occasion, from all levels of society. Smyth, in fact, highlighted a facet of Henry Berkeley's character which could not have been gleaned from the Caludon accounts. He was clearly impressed by Henry's sociability and lack of snobbishness and aloofness, unusual

for a man of his social standing.

ortunately the accounts record not only the purchase of material objects, but also indirectly reveal the events which took place within the walls of Caludon, given an invaluable additional perspective by Smyth. The Berkeleys were hospitable, known for lavish entertainments at which music, singing and dancing, as well as acting, played an important part. They shared their pleasures with their guests, invited, depending on the occasion, from all levels of society. Smyth, in fact, highlighted a facet of Henry Berkeley's character which could not have been gleaned from the Caludon accounts. He was clearly impressed by Henry's sociability and lack of snobbishness and aloofness, unusual

for a man of his social standing.

It would not be difficult to imagine this scene taking place in the great hall at Caludon, the Lord's table at the upper end, but Henry happy to sit himself on occasions at the lower end, presumably near the porch and its draughty cross-passage. With his top table occupied by guests of both 'first' and 'mean' rank, he would position himself at their junction rather than in the midst of his social peers. The reference to 'near the salt' is interesting, as social status was usually reflected by how far away one sat from the salt, an expensive commodity kept in an elaborate cellar on the top table.

The food provided at these feasts was lavish and plentiful; roasted boar, peacock (served with its tail display intact), brawn, frumenty (boiled wheat with porridge) fruits, jellies, blancmange and all the wines and ales which could be mustered. The kitchen at Caludon was probably stocked with the produce of its own demesne, and tenant farms, but it also purchased from farther afield, through local suppliers. So we find '3 barrells of white hearinge at 34s the barrel and '2 Cades of red hearinge at 16s,'1 cade of sprats' (5s) and three dozen salted eels purchased from Walker, a fishmonger of Coventry (May 1595). Mutton was purchased from Derby Fair, but from more exotic climes and therefore expensive, came 30 lemons and 50 oranges supplied by a John Harbert for 5s 4d (April 1605). In June 1596 a wide array of spices and delicacies was acquired for 18s 3d.

A year earlier a pound of carroway seeds was supplied at a cost of 16d. Many spices, owing to the long distances they travelled from their growing areas, were costly, but to the aristocracy who could afford them, spices were an intrinsically desirous commodity. Nevertheless, as today, spices were primarily sought to give food extra and exotic flavour and it is a myth that they were used in earlier times to mask the taste of rotten meat. The Lord Henry's dog may not have had spices added to his meat, but it was well fed with horse flesh, a carcass, costing 14d, transported to Caludon in March 1595/6 for an extra 6d. In the month before two strikes of barley, costing 6s, were also intended as dog feed.

Henry was an enthusiastic patron of the arts especially dance and drama, and Caludon frequently hosted musicians and bands of actors. Both Henry and Katherine were themselves musically trained and Lady Katherine was a particular lover of the lute. Smyth remarked that:

This was a skill that they wished to impart to their son, Thomas, and in November 1595, when he was twenty years of age, 'Mills the Lute player' was employed for three weeks to teach 'Master Berkeley to play on the Lute' for which Mills was paid 15s. Even in the years following Katherine's death in 1596 Henry still employed players to perform before him at Caludon.

The accounts are, in fact, an important source for late Tudor and early Stuart court entertainers - musicians, dancers and actors (Fig 5). Peter Greenfield analysed nearly a hundred payments or 'rewards', as they were called, made to them. Published in 1983, this is the first known occasion that the accounts have been used as a historical source. Unfortunately Greenfield did not have access at the time to the middle volume in the sequence (GBB 108), which recorded in January 1598/9 the engagement of the services of John Dowland, England's pre-eminent lute player.

This was reported more recently by Mike Ashley, a lutenist himself and member of the Lachrimae Consort, a group of players specialising in Elizabethan music (Fig 6). Dowland was both an extraordinary lute player and a song writer of great reputation. He recently achieved widespread popularity when the pop singer, Sting, produced an album of his songs and learnt to play the lute for that purpose. In his day Dowland was, however, the most famous lute player in Europe and his melancholy songs such as Flow my Tears, Come Heavy Sleep and I Saw My Lady Weep are amongst the finest songs written in the English language. Dowland was a Catholic, which may explain why he performed personally for the Berkeleys when in fact he was supposed to be in Denmark in the employ of King Christian IV. It is possible that he returned to England on leave, perhaps at the behest of Lord Hunsdon, the father-in-law of Henry's son Thomas, who knew Dowland from his diplomatic post at the Langrave of Hessen. 40s was paid in January 1598/9 to Dowland and his 'Consorte' (a group of players), probably for performing at Caludon at Christmas (Fig 7). This in itself is interesting, for it is the only known reference to Dowland playing with a consort; it has always been assumed that he was a brilliant solo lute player and writer of magnificent songs.

John Dowland was the most famous name to appear in the Caludon accounts, but they are full of payments to other individual performers and groups: musicians, trumpeters, dancers (one a sword dancer), bearwards, fools and morris dancers. Anonymous musicians were paid £3 for playing at Christmas 1592 (Jan 1592/3). Two years later the cost of hiring a group of unnamed musicians was £4 and taberer (a drummer), 10s (Jan 1594/5). In December 1595 musicians performed in 'ye lord [Henry Berkeley's] chamber' and a group of 'singars of Coventry' were rewarded with 3s 4d and a blind harper given 2s. Throughout the 1590s there are regular payments to musicians for performing at Christmas, undoubtedly the major festival in the year to be celebrated in this way.

Troupes of actors regularly visited Caludon, making it one of the cultural centres of Warwickshire during this period. In December 1593 a company known as the 'Earl of Derby's players' performed at Caludon and in the following July another company, the Queen's players, was paid 12s for their appearance. Christmas 1600 was particularly hectic artistically with the arrival of three groups: Lord Dudley's, Lord Huntingdon's and, once again, the Queen's players. After 1600 the number of visiting acting companies declines sharply, but musicians remain popular. Other kinds of performers replaced the actors, such as the fools of Lord Dudley (June 1604) and of Lord Bedford (Jan 1603) and a Morris dancer, who came from Kenilworth (May 1605). In contrast to the sparkling and lively entertainments that were staged regularly at Caludon, the accounts record a much more solemn occasion. The sombre but spectacular funeral of Lady Katherine Berkeley that took place in 1596, has already been described in a previous chapter, but we now know of some of the preparations that were made for this event. At Caludon a total of £33 18s 8d was paid out for:

Henry Berkeley's study had been prepared to receive Katherine's body after it had been 'opened up and preserved' by David Astley and Henry Hickmen (paid £7 7s 2d, April 1596). Katherine was laid out under a canopy or 'tent', around which, presumably, chairs were arranged for the numerous mourners that came to pay their respects. Some visitors stayed overnight, and the more important for longer, and feather beds had to be repaired to cope with the demand. Three shillings were given to the 'Ringers of Sowe' [church] for ringing a doleful peel in Lady Katherine's memory (April 1596).

The financial accounts of a great historic house could at first glance be regarded as dry and uninteresting, not worthy of attention except for scholars of abstruse historical detail and minutiae. This chapter, it is hoped, has demonstrated how rich a source such documents can be and how their analysis can enliven the history of any time or place where the facts are sparse and the physical remains insubstantial. It is no longer so difficult to imagine what life was like at Caludon Castle (or Caludon House as it was called at this time) at one of its high points in its history - the turn of the seventeenth century. These three volumes of accounts are a goldmine awaiting the extraction of yet more interesting revelations and justify a publication entirely devoted to the life of Lord Henry Berkeley at Caludon.

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026