|

Index...

|

espite the government's reluctance to publicly declare that another war was likely, as early as 1934 preparations were being quietly made in case the unthinkable happened. In the Air Defence exercises of that year, in addition to London - Coventry and Birmingham were singled out as the most likely enemy bombing targets, and forming a defence against air attack for London and the Midlands was made a priority.

espite the government's reluctance to publicly declare that another war was likely, as early as 1934 preparations were being quietly made in case the unthinkable happened. In the Air Defence exercises of that year, in addition to London - Coventry and Birmingham were singled out as the most likely enemy bombing targets, and forming a defence against air attack for London and the Midlands was made a priority.

Coventry's susceptibility was no surprise. Since the growth here of the cycle and motor trades in the closing decades of the 19th century, Coventry, with all its engineering skills and manufacturing capacity, had become the obvious place for the mass production of many war-related products. The First World War had prompted a build up of armament factories in the city, and this was ramped up once again with the imminent arrival of World War Two.

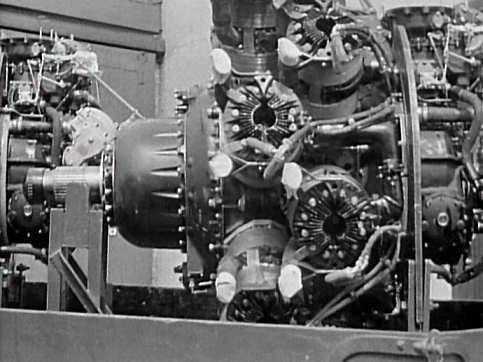

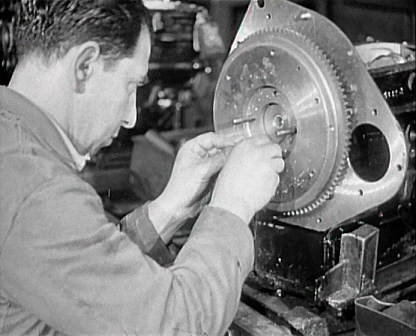

Most of our factories were turned over to war production, and among these were; Dunlop, who manufactured wheel discs, brakes, gun mechanisms and even barrage balloons, Hawker Siddeley, Vickers Armstrong, Armstrong Whitworth and Rolls Royce - producing aeroplanes, engines and all associated parts - including the complete Whitley twin engined heavy Bomber. Humber and Daimler also made armoured troop transporters and scout cars, and Cash's and Courtaulds produced materials for things like parachutes. G.E.C. provided radio equipment, including the then new VHF sets, and British Thompson-Houston were turning out electro-magnetic components, such as magnetos and dynamos.

The Coventry manufacturing legend, Sir Alfred Herbert, was of course involved, providing essential machine tools - as were Coventry Climax, Coventry Gauge and Tool, and countless other smaller firms around the city, all helping towards the war effort in every conceivable way.

Altogether, Coventry's contribution to war production was immense, so nobody could have been surprised that our city had long been earmarked as a likely target for an attack by the Luftwaffe. Nobody, however, could have predicted the level of devastation that a single raid could bring when it actually came.

Taking into account the above reasons, Coventry could definitely be considered a military target, so chances are, an attack on a large scale would have happened sooner or later. However, it seems that this particular mid-November 'blitz' had its seeds sown a few days earlier, on Friday 8th November. That night, the RAF bombed Munich, the homeland of the Nazi Party. It wasn't a particularly effective raid from a strategic point of view, but Hitler saw this as a personal insult, and it inflamed his wish to seek revenge in the most devastating way he knew. The Fuhrer was infuriated, and a city in England was about to pay the price. And what a price!

However, even allowing for our manufacturing targets, the justification for the bombing methods used in this raid is questionable and will be discussed further. The military usefulness of the raid was not great - of the factories that were destroyed, most were in or near the city centre, and comprised mainly smaller firms. The larger factories farther out were generally back to full capacity within weeks, and most multiplied their output after the raid.

Although Hitler could use the military tag to try to justify his actions, it's quite plain that this raid, and indeed the blitz on English cities as a whole, was done in the hope that the sheer horror of his actions would bring our citizens to their knees. When we consider how horrific these nights were, with people losing family, friends, homes, their town centre, and indeed everything they'd ever owned or worked for, it's not surprising that the Germans felt they could batter us into submission. Before the raids began, even psychological experts in our own country thought that the general populace would be unable to cope with such actions, and that absolute mental breakdown, panic and anarchy would be the outcome. As has been said by many people before, this island race is made of sterner stuff, and better should have been expected.

In support of the idea that this was primarily a terror raid, we can look at the some of the bombing methods. The Luftwaffe had accurate maps of Coventry, so they would've been aware that wiping out Coventry's city centre, an area roughly half by three quarters of a mile, was largely going to destroy shops, churches and small businesses laid out around our mainly medieval street pattern. Once the initial "Pathfinder" bombers had dropped their flares and incendiaries to light up the target area, the subsequent bombers not only followed the path to the area, but actually flew in an alternate north-south then east-west pattern, to clinically and methodically raze the whole town centre to the ground.

Indeed, when one looks at the photographs of the destruction (and there are plenty in the following pages), it makes you wonder how anything was left standing at all when it was over!

In addition to this, the bombing of Coventry certainly cannot be considered an isolated incident regarding behaviour of a non-military character. In 1942 the Germans carried out a particularly cynical series of attacks that became known as the Baedeker raids, which specifically targeted places of historical merit listed in their Baedeker guide book - targets which they acknowledged were of no strategic military importance. Coventry, however, was not included among these raids, perhaps because it had already been dealt with in 1940. The Baedeker guide did include a city centre plan of Coventry, though, and I have a copy of an original map from 1910 for you to view on my Old map scans page.

Website by Rob Orland © 2002 to 2026